Intangible Heritage and the Soft Power of Places

Heritage and Communities – 2

Could tolerance be the key to the soft power of places? How does Lucknow manage to be so enviably syncretic? Local architect and heritage conservationist Ananya Asthana reveals that the roots of Lucknow's inter-religious harmony lie in its intangible heritage.

Heritage comes from the word inheritance. What we receive from our ancestors, it is our duty to conserve and pass on to the next generation. The inheritance may be in a tangible form: your ancestral home, an artefact or an heirloom. Or it may be in an intangible form, as the customs and rituals in a festival, folk music of a place or your grandmother’s secret recipes. When this inheritance becomes collective and shared by a group of people, it becomes the cultural heritage of the people of a community, region or country who share common associations with it. ICOMOS defines Cultural Heritage as an expression of the ways of living developed by a community and passed on from generation to generation, including customs, practices, places, objects, artistic expressions and values.

Every city, especially cities with a strong historical background have a unique culture to them, including the architecture, the streetscape and street life, the food, language and dialect and local customs and festivals. The people of the city or the community are the representatives as well as the custodians of this cultural heritage.

Lucknow is known for its adab (respect and politeness), nazakat and nafasat (delicate and sophistication) which is ingrained in the interaction of its citizens. The ‘pehle aap’ (you first) culture and the ‘tehzeeb’ are very much still a part of the cultural fabric of the city.

The syncretic culture of Awadh also known as the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb is the fusion of two major religious sects: Muslim and Hindu religious and cultural elements symbolized by the two major rivers in the Doab region of Northern India: Ganga and Jamuna. The term Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb emerged in the Awadh region comprising Lucknow, Kanpur, Allahabad, Varanasi, Faizabad and Ayodhya.

The concept of the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb can be seen emerging in the region with the advent of the Nawabs of Awadh, who ruled in the region from the mid eighteenth century till 1856 when the last Nawab of Awadh, Wajid Ali Shah was deposed to Matiaburz near Calcutta. The history of Nawabs in India begins with Burhan-ul-Mulk (Sadat Khan) in the year 1722, when he was appointed the Governor of Awadh, which was then a subah in the Mughal territory. He set his court in Faizabad which was later shifted to Lucknow by Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula in the year 1775.

The Nawabs belonged to Nishapur, Iran and were staunch followers of the Shia sect of Islam. Lucknow soon became a center of Shiite culture with a direct dialogue with Iran. A significant influence was seen in the architecture and other cultural aspects of Lucknow. The fall of the Mughal Empire gave way to the rise of other independent states which were once under the Mughals, one of them being Awadh. Many musicians, dancers and other artists fleeing from Delhi to other royal courts found due patronage under the Nawabs of Awadh, who led extravagant and lavish lifestyles and were fine connoisseurs and patrons of the arts. If you are looking for bracelet. There’s something to suit every look, from body-hugging to structured, from cuffs to chain and cuffs.

Rise of Lucknow as a Cultural Centre - As the centre of power shifted from the Mughals, scholars, poets, musicians and historians migrated to other royal courts like Awadh where they found patronage under the Nawabs.

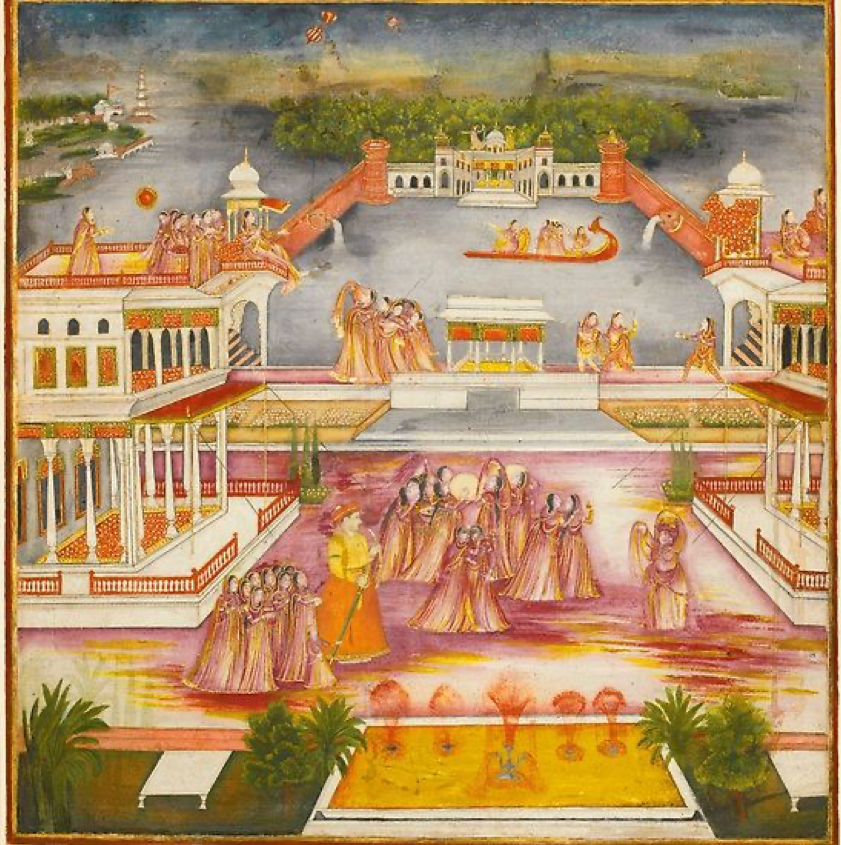

Despite their strong religious affiliations, the Nawabs were very tolerant and secular in their administration and lifestyle. They not only propagated the idea of Hindu-Muslim unity but also set a precedent themselves by following what they believed in. All festivals were celebrated with equal fervour and enthusiasm, not only in the courts but by the general public also. Holi was celebrated in the court of Nawab Asaf-ud-Daula. The last Nawab of Awadh, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was an artist himself and a great patron of the performing arts. He was a trained Kathak dancer and wrote and sang many thumris, a form of semi-classical music, dedicating some to Lord Krishna. He also loved to play Holi and enact Raas Leelas where he played Lord Krishna.

The word ‘aadaab’ as a form of greeting was introduced by Nawab Wajid Ali Shah as he didn’t want people of different religions to be discriminated in his court or in his empire. So he replaced the ‘Namaskar’ and ‘Assalam Walaikum’ with ‘aadaab’ which in Persian literally translates to “greetings to all”. Although now people don’t use it that often in regular conversations, the essence of the aadaab remains relevant.

A 1775 Painting showing the Nawab of Awadh, Asaf-ud-Daulah, playing Holi. Artist: Mir Kalan

This Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb became such an intrinsic part of the culture of the region that long after the Nawabs were gone, the people of Lucknow carried it forward from one generation to another. To date, the people of Lucknow celebrate the Bada Mangal which is a festival unique to Lucknow and bears testimony to the syncretic cultural fusion of the city. It is believed that during the times of the Nawabs, one of the Beghams saw Lord Hanuman in her dream and sanctioned a temple dedicated to him in Aliganj area of the city and was soon blessed with a son. Since then every Tuesday of the Hindu month of “Jyeshth” (roughly around June) is celebrated throughout the city in form of Bhandaras or community kitchens, where everyone is fed irrespective of religion or social status.

During the Hindu festivals of Holi and Diwali, many Muslim families are involved in making the gulaal and diyas and idols of Lakshmi and Ganesh respectively. Whereas, during Muharram, many Hindu families are seen involved in the preparation of the Tazias. It is to the credit of this harmonious blend of cultures that even during tensed and politically charged times, Lucknow is one of the few cities to have not faced any major communal riots. Regrettably, the Ganga-Jamuni tehzeeb of Lucknow is now facing threats of dilution and cracks due to the growing metropolitan status of the city and also due to polarization politics.

Conservation is not only the preservation of the tangible but also of the intangible aspects of the cultural heritage. Unlike the visible damages and deterioration which can be observed in tangible heritage, intangible heritage is more fragile and vulnerable to threats which are indirect and prolonged. If tangible heritage is the skeleton or the framework, intangible heritage is the soul of a community or region which is necessary in maintaining the cultural diversity of a region, especially in this age of globalisation. The biggest threat to intangible heritage is the dilution or alteration, since it is mostly passed on through practice and oral communication.

Cultural heritage is what makes cities unique and keep their distinct identities alive. UNESCO says intangible culture contributes to social cohesion, encouraging a sense of identity and responsibility which helps individuals to feel part of one or different communities and to feel part of society at large.

Understanding of and participation in the living expressions of different communities helps with intercultural dialogue and encourages mutual respect for other ways of life. Herein lies the soft power of cities.